More Reefer Madness

By Eric Schlosser, The Atlantic Monthly; April 1997; More Reefer Madness; Volume 279, No. 4; pages 90-102.

EIGHT years ago Douglas Lamar Gray bought a pound of marijuana in a room at the Econo Lodge in Decatur, Alabama. He planned to keep a few ounces for himself and sell the rest to some friends. Gray was a Vietnam veteran with an artificial leg. As a young man, he’d been convicted of a number of petty crimes, none serious enough to warrant a prison sentence. He had stayed out of trouble for a good thirteen years. He now owned a business called Gray’s Roofing and Remodeling Service. He had a home, a wife, and a two-year-old son. The man who sold him the drug, Jimmy Wilcox, was a felon just released from prison, with more than thirty convictions on his record. Wilcox was also an informer employed by the Morgan County Drug Task Force. The pound of marijuana had been supplied by the local sheriff’s department, as part of a sting. After paying Wilcox $900 for the pot, which seemed like a real bargain, Douglas Lamar Gray was arrested and charged with “trafficking in cannabis.” He was tried, convicted, fined $25,000, sentenced to life in prison without parole, and sent to the maximum-security penitentiary in Springville, Alabama — an aging, overcrowded prison filled with murderers and other violent inmates. He remains there to this day. Under the stress of his imprisonment Gray’s wife attempted suicide with a pistol, survived the gunshot, and then filed for divorce. Jimmy Wilcox, the informer, was paid $100 by the county for his services in the case.

Gray’s punishment, although severe, is by no means unusual in the United States. The laws of at least fifteen states now require life sentences for certain nonviolent marijuana offenses. In Montana a life sentence can be imposed for growing a single marijuana plant or selling a single joint. Under federal law the death penalty can be imposed for growing or selling a large amount of marijuana, even if it is a first offense. The rise in marijuana use among American teenagers became a prominent issue during last year’s presidential campaign, fueled by Republican accusations that President Bill Clinton was “soft on drugs.” Teenage marijuana use has indeed grown considerably since 1992; by one measure it has doubled. But that increase cannot be attributed to any slackening in the enforcement of the nation’s marijuana laws. In fact, the number of Americans arrested each year for marijuana offenses has increased by 43 percent since Clinton took office. There were roughly 600,000 marijuana-related arrests nationwide in 1995 — an all-time record. More Americans were arrested for marijuana offenses during the first three years of Clinton’s presidency than during any other three-year period in the nation’s history. More Americans are in prison today for marijuana offenses than at any other time in our history. And yet teenage marijuana use continues to grow.

The war on drugs, launched by President Ronald Reagan in 1982, began as an assault on marijuana. Its effects are now felt throughout America’s criminal-justice system. In 1980 there were almost twice as many violent offenders in federal prison as drug offenders. Today there are far more people in federal prison for marijuana crimes than for violent crimes. More people are now incarcerated in the nation’s prisons for marijuana than for manslaughter or rape.In an era when the fear of violence pervades the United States, small-time pot dealers are being given life sentences while violent offenders are being released early, only to commit more crimes. The federal prison system and thirty-eight state prison systems are now operating above their rated capacity. Attempts to reduce dangerous prison overcrowding have been hampered by the nation’s drug laws. Prison cells across the country are filled with nonviolent drug offenders whose mandatory-minimum sentences do not allow for parole. At the same time, violent offenders are routinely being granted early release. A recent study by the Justice Department found that in 1992 violent offenders on average were released after serving less than half of their sentences. A person convicted of murder in the United States could expect a punishment of less than six years in prison. A person convicted of kidnapping could expect about four years. Another Justice Department study revealed that almost a third of all violent offenders who are released from prison will be arrested for another violent crime within three years. No one knows how many violent crimes these released inmates commit without ever being caught. In 1992 the average punishment for a violent offender in the United States was forty-three months in prison. The average punishment, under federal law, for a marijuana offender that same year was about fifty months in prison.

Even legislation aimed at reducing violent crime has been subverted by the legal underpinnings of the drug war. According to a report by the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice, California’s much-heralded “three strikes, you’re out” law has imprisoned twice as many people for marijuana offenses as for murder, rape, and kidnapping combined.

The vehemence of marijuana’s opponents and the harsh punishments routinely administered to marijuana offenders cannot be explained by a simple concern for public health. Paraplegics, cancer patients, epileptics, people with AIDS, and people suffering from multiple sclerosis have in recent years been imprisoned for using marijuana as medicine. The attack on marijuana, since its origins early in this century, has in reality been a cultural war — a moral crusade in defense of traditional American values. The laws used to fight marijuana are now causing far more harm to those values than the drug itself. In order to eliminate marijuana use, state and federal legislators have sanctioned an enormous increase in prosecutorial power, the emergence of a class of professional informers, and the widespread confiscation of private property by the government without trial — legal weapons reminiscent of those used in the former Soviet-bloc nations. The long prison sentences given to growers and dealers have pushed marijuana prices skyward, creating a domestic industry whose annual revenues now rival those of cotton, soybeans, or corn. U.S. public officials, like their counterparts in Mexico, Colombia, and Bolivia, are being corrupted with drug money. Millions of ordinary Americans have been arrested for marijuana offenses in the past decade, and hundreds of thousands have been imprisoned, yet marijuana use is increasing and has regained its status as a symbol of youthful rebellion. Instead of debating the wisdom of our current policies, members of Congress and of the Administration are competing to see who can appear toughest on drugs. For years the war on drugs has been driven by political concerns, without regard to its consequences. But at the state and local levels, where the costs of that war are most keenly felt and unlikely alliances have begun to form, there are signs that madness may give way to common sense.

The Legacy of Len BiasTHE 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act marked a profound shift not only in America’s drug-control policy but also in the workings of its criminal-justice system. The bill greatly increased the penalties for federal drug offenses. More important, it established mandatory-minimum sentences, transferring power from federal judges to prosecutors. The mandatory minimums were based not on an individual’s role in a crime but on the quantity of drugs involved. Judges in such cases could no longer reduce a prison term out of mercy or compassion. Prosecutors were given the authority to decide whether a mandatory-minimum sentence applied.

This new law did not represent the culmination of a careful deliberative process. Nor did it reflect the thinking of the nation’s best legal minds. The mandatory-minimum provisions were written and enacted in a matter of weeks without a single public hearing. The most important drug legislation in a generation — the enforcement of which would more than triple the size of the federal-prison population and whose sentencing philosophy would influence state drug laws across the country — was prompted by the death of a popular basketball player shortly before a congressional election.Len Bias was a local hero in Washington, D.C., clean-cut and all-American, a University of Maryland basketball star who had been drafted by the Boston Celtics at the age of twenty-two. On June 17, 1986, Bias attended a ceremony in Boston to sign a contract with the Celtics. Two days later he died of heart failure, allegedly caused by crack cocaine. When Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill returned to Boston for the Fourth of July congressional recess, everyone seemed to be talking about the death of the Celtics’ first-round draft pick. As fears of crack cocaine swept the nation, O’Neill grew worried that the Democratic Party might be labeled soft on drugs. He returned to Washington in mid-July determined to pass an omnibus drug-control bill before the upcoming election. The legislation had to be drafted within a month. Eric E. Sterling, who was then the assistant counsel for the House Subcommittee on Crime, recently told me that staff members scrambled to assemble a bill. The process of selecting drug quantities to trigger the mandatory-minimum sentences was far from scientific, according to Sterling: “Numbers were being picked out of thin air.”

The drug-control bill left the subcommittee in mid-August, while many academics and government officials were away on vacation. There had been little time to study the potential costs of the legislation or its ramifications for the criminal-justice system. In the absence of public hearings there had been no input from federal judges, prison authorities, or drug-abuse experts. President and Mrs. Reagan were calling for tough new drug-control measures, and House Democrats rushed to provide them. Only sixteen congressmen voted against the bill, which passed in the Senate by a voice vote. Reagan signed the final version of the bill on October 27, just a week before Election Day.In Smoke and Mirrors, which was published last year, Dan Baum, a former Wall Street Journal reporter, gives a definitive account of the politics surrounding Reagan’s war on drugs. Conservative parents’ groups opposed to marijuana had helped to ignite the Reagan Revolution. Marijuana symbolized the weakness and permissiveness of a liberal society; it was held responsible for the slovenly appearance of teenagers and their lack of motivation. Carlton Turner, Reagan’s first drug czar, believed that marijuana use was inextricably linked to “the present young-adult generation’s involvement in anti-military, anti-nuclear power, anti-big business, anti-authority demonstrations.” A public-health approach to drug control was replaced by an emphasis on law enforcement. Drug abuse was no longer considered a form of illness; all drug use was deemed immoral, and punishing drug offenders was thought to be more important than getting them off drugs. The drug war soon became a bipartisan effort, supported by liberals and conservatives alike. Nothing was to be gained politically by defending drug abusers from excessive punishment.

Drug-control legislation was proposed, almost like clockwork, during every congressional-election year in the 1980s. Election years have continued to inspire bold new drug-control schemes. On September 25 of last year Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich introduced legislation demanding either a life sentence or the death penalty for anyone caught bringing more than two ounces of marijuana into the United States. Gingrich’s bill attracted twenty-six co-sponsors, though it failed to reach the House floor. A few months earlier Senator Phil Gramm had proposed denying federal welfare benefits, including food stamps, to anyone convicted of a drug crime, even a misdemeanor. Gramm’s proposal was endorsed by a wide variety of senators — including liberals such as Barbara Boxer, Tom Harkin, Patrick Leahy, and Paul Wellstone. A revised version of the amendment, limiting the punishment to people convicted of a drug felony, was incorporated into the welfare bill signed by President Clinton during the presidential campaign. Possessing a few ounces of marijuana is a felony in most states, as is growing a single marijuana plant. As a result, Americans convicted of a marijuana felony, even if they are disabled, may no longer receive federal welfare or food stamps. Convicted murderers, rapists, and child molesters, however, will continue to receive these benefits.

Forfeitures and Informers

FEDERAL prosecutors now have an extraordinary amount of power in drug cases. A U.S. attorney can determine the eventual punishment for a drug offense by deciding what quantity of drugs to list in the indictment, whether a mandatory-minimum sentence should apply, and whether to press charges at all. Drug offenses differ from most crimes in being subject to federal, state, and local laws. The federal government could prosecute any and every marijuana offender in the United States if it so desired, but in a typical year it charges fewer than one percent of those arrested. By choosing to enter a particular case, a federal prosecutor can greatly affect the penalty for a marijuana crime. In 1985 Donald Clark, a Florida watermelon farmer, was arrested for growing marijuana, convicted under state law, and sentenced to probation. Five years later the local U.S. attorney decided to prosecute Donald Clark under federal law for exactly the same crime. Clark was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison without parole. A Justice Department spokesman quoted in Smoke and Mirrors later defended the policy of trying drug offenders twice for the same crime: “The intent is to get the bad guys off the street with apologies to none.”

Under civil forfeiture statutes passed by Congress in the 1980s, the federal government now has the right to seize real estate, vehicles, cash, securities, jewelry, and any other property connected to a marijuana offense. The government need not prove that the property was bought with the proceeds of illegal drug sales, only that it was used — or was intended to be used — in a crime. A yacht can be seized if a single joint is discovered on it. A farm can be seized if a single marijuana plant is found growing there. According to Steven B. Duke, a professor at Yale Law School, in some cases a house can be seized if it contains books on marijuana cultivation. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled last year that the government can seize property even when its owner had no involvement in, or knowledge of, the crime that was committed. When property is seized, its legal title passes instantly to the government. The burden of proving its “innocence” falls upon the original owner. In 1994 assets worth roughly $1.5 billion were forfeited under state and federal laws. In perhaps 80 percent of those cases the owner was never charged with a crime. The forfeiture statutes have deepened the injustice of the war on drugs by enabling wealthy defendants to surrender property in return for shorter sentences; plea-bargain negotiations often turn into haggling sessions worthy of a Middle Eastern souk.The proceeds from an asset forfeiture are divided among the law-enforcement agencies involved in the case, a policy that invites the abuse of power. Former Justice Department officials have admitted in newspaper interviews that many forfeitures are driven by the need to meet budget projections. The guilt or innocence of a defendant has at times been less important than the availability of his or her assets. In California thirty-one state and federal drug agents raided Donald P. Scott’s 200-acre Malibu ranch on the pretext that marijuana was growing there. Scott was inadvertently killed during the raid. No evidence of marijuana cultivation was discovered, and a subsequent investigation by the Ventura County District Attorney’s Office found that the drug agents had been motivated partly by a desire to seize the $5 million ranch. They had obtained an appraisal of the property weeks before the raid. In New Jersey, Nicholas L. Bissell Jr., a local prosecutor known as the Forfeiture King, helped an associate to buy land seized in a marijuana case for a small fraction of its market value. In Connecticut, Leslie C. Ohta, a federal prosecutor known as the Queen of Forfeitures, seized the house of Paul and Ruth Derbacher when their twenty-two-year-old grandson was arrested for keeping marijuana there. Although the Derbachers were in their eighties, had owned the house for almost forty years, and had no idea that their grandson kept pot in his room, Ohta insisted upon forfeiture of the house. People should know, she argued, what goes on in their own home. Not long after, Ohta’s eighteen-year-old son was arrested for selling LSD from her Chevrolet Blazer. Allegedly, he had also sold marijuana from her house in Glastonbury. Ohta was quickly transferred out of the U.S. attorney’s forfeiture unit — but neither her car nor her house was seized by the government.

The only way a defendant can be sure of avoiding a mandatory-minimum sentence under federal law is to plead guilty and give “substantial assistance” in the prosecution of someone else. The willingness to turn informer has become more important to a drug offender’s fate than his or her role in a crime. The U.S. attorney, not the judge, decides whether the defendant’s cooperation is sufficient to warrant a reduction of the sentence. Although this system helps to avoid expensive trials and provides evidence for future indictments, it also leads to longer prison terms for the minor participants in a drug case. Kingpins have a great deal of information to provide, whereas drug couriers often have none.A little-known provision of the forfeiture laws rewards confidential informers with up to 25 percent of the assets seized as a result of their testimony. During the 1980s the United States developed a wealthy and industrious class of professional informers. In 1985 the federal government spent $25 million on informers. Last year it spent more than $100 million.Informing on others has become not just a way to avoid punishment but a way of life. In major drug cases an informer can earn a million dollars or more. A recent investigation by the National Law Journal found that the proportion of federal search warrants relying exclusively on unidentified informers nearly tripled from 1980 to 1993, increasing from 24 percent to 71 percent. The growing reliance on informers has given an unprecedented degree of influence to criminals who have a direct financial interest in gaining convictions. Informers have been caught framing innocent people. Law-enforcement agents have been caught using nonexistent informers to justify search warrants

“Criminals are likely to say and do almost anything to get what they want,” Stephen S. Trott, a federal judge who was the chief of the Justice Department’s Criminal Division during the Reagan years, says in the National Law Journal. “This willingness to do anything includes not only truthfully spilling the beans on friends and relatives but also lying, committing perjury, manufacturing evidence, soliciting others to corroborate their lies with more lies, and double-crossing anyone with whom they come into contact, including — and especially — the prosecutor.”The legal and monetary rewards for informing on others have even spawned a whole new business: the buying and selling of drug leads. Defendants who hope to avoid a lengthy mandatory-minimum sentence but who have no valuable information to give prosecutors can now secretly buy information from vendors on the black market. According to Tom Dawson, a prominent Kansas defense attorney, some professional informers now offer their services to defendants in drug cases for fees of up to $250,000.Most of the people being imprisoned for marijuana offenses are ordinary Americans without important information to provide, large assets to trade, or the income to pay for high-priced attorneys. Allen St. Pierre, the deputy director of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, has spoken to literally thousands of people who have been arrested for pot-related offenses. He receives about a hundred phone calls each week from people who are losing their jobs, losing their houses, feeling desperate for advice. They tend to be working people: house painters, clerks, carpenters, and mechanics. Their cases tend to be handled, or mishandled, by family attorneys with little knowledge of the marijuana laws. America’s prisons are full of poor and working-class marijuana offenders.

Children of the upper middle class are rarely sent to prison for marijuana offenses today. Their parents usually enroll them in private drug-treatment programs before trial and hire attorneys who specialize in drug cases. Privileged young men and women are usually treated more leniently in court. The daughter of Judge Rudolph Slate, the man who sentenced Douglas Lamar Gray to life for buying a pound of marijuana, was later arrested for selling the drug. She was granted youthful-offender status. The records in her case have been sealed; most likely she received probation. The son of Indiana Congressman Dan Burton, an outspoken proponent of life sentences for some marijuana-related crimes, was arrested for transporting nearly eight pounds of pot from Louisiana to Indiana in the trunk of his car. Six months later Danny L. Burton II was arrested again, this time at his Indianapolis apartment, where police found thirty marijuana plants and a shotgun with six shells. Federal prosecutors declined to press charges against Burton’s son; Indiana prosecutors gained dismissal of the charges against him; and a Louisiana judge sentenced him to community service, probation, and house arrest. As chairman of the House Government Reform and Oversight Committee, Burton is now leading the investigation of ethical lapses in the Clinton Administration. He will not comment on his son’s case.The harshest punishments are given to people who won’t cooperate with the government. The pressure to inform on others is immense — as is the cost of resisting it. In 1993 Jodie Israel was arrested for marijuana possession and balked at testifying against her husband, a Rastafarian marijuana trafficker. Federal prosecutors in Montana threatened her with a long prison sentence. Although Israel possessed only eight ounces of marijuana at the time of her arrest, under the broad federal conspiracy laws she could be held liable for many of her husband’s crimes. Israel was thirty-one years old, the mother of four young children. She had never before been charged with any crime. Judge Jack Shanstrom warned her in court that without a promise of cooperation “you are not going to see your children for ten plus years.” Nevertheless, Israel refused to testify against her husband. She was sentenced to eleven years in federal prison without parole. Her husband was sentenced to twenty-nine years without parole. Her children were scattered among various relatives

“A Matter of Practicality”

IN 1988 State Senator Stewart J. Greenleaf wrote the bill that made tough mandatory-minimum drug sentences part of Pennsylvania law. Greenleaf, a Republican from rural Montgomery County, is now the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee in Pennsylvania — and an outspoken critic of mandatory-minimum sentences. “These laws just haven’t worked as we planned,” he now admits. Politicians are refusing to acknowledge the true cost of the nation’s drug laws. “We’re not being honest,” Greenleaf says, “to the public or to ourselves.”

In adopting mandatory-minimum sentences, Pennsylvania had simply followed the federal government’s lead, aiming to give long prison terms to major drug dealers. Instead the state’s prisons have been flooded with low-level drug offenders who cannot be paroled. Over the past decade the state’s prison population has doubled. Its prison system is now operating at 54 percent above capacity. In order to keep pace with the current rate of incarceration, Pennsylvania will have to open a new prison every ninety days. Each new prison cell costs about $110,000 to build and about $25,000 a year to maintain. At the moment nearly 70 percent of the inmates in Pennsylvania’s prisons are nonviolent offenders. Convicted murderers granted early release have gone on a number of well-publicized killing sprees. “Expensive prison space must be held for those who are truly violent or career criminals,” Greenleaf has come to believe. “This problem has transcended party lines and social ideologies; it is a matter of practicality and fiscal responsibility.”As prisons become more and more overcrowded, state legislators across the country are exploring a wide range of alternative sentences. At least half a dozen states now allow low-level drug offenders to avoid prison terms by entering drug-treatment programs. In Pennsylvania, where perhaps 80 percent of all crimes are being committed by either alcohol or drug abusers, the state District Attorneys Association and the local chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union both advocate emphasizing substance-abuse treatment rather than imprisonment. Greenleaf favors treatment programs, intensive probation, and ninety-day “shock incarceration” in jail or boot camps for most drug offenders — alternatives that are far less expensive than sending people to prison. Although he worries about the political fallout from his stance, he will not budge. “We have to be smart about whom we incarcerate,” Greenleaf says, “and not waste taxpayers’ money.”

The trend toward alternative sentences for drug offenders has lately gained support in some unexpected quarters. Arizona’s recently passed Proposition 200 not only allows the medicinal use of marijuana but also has reformed the state’s approach to drug control. Since the early 1980s Arizona had aggressively pursued a drug strategy of “zero tolerance,” administering harsh punishments for illegal drug use, not just for drug trafficking and possession. Failing a urine test was grounds for prosecution in Arizona: a person could face criminal charges in Phoenix for a joint smoked in Philadelphia days or even weeks before. Arizona’s prisons grew overcrowded, and tent cities rose in the desert to house inmates. Proposition 200 declared that “drug abuse is a public health problem” and vowed to “medicalize” the state’s drug-control policy. In order to free up prison cells for violent offenders, the initiative called for the immediate release of all nonviolent prisoners who had been convicted of drug possession or use. It called for drug treatment, drug education, and community service instead of prison terms for nonviolent minor drug offenders. And it called for the creation of a state Drug Treatment and Education Fund through an increased tax on alcohol and tobacco. Proposition 200 was endorsed by aging hippies, former members of the Reagan Administration, the retired Democratic senator Dennis DeConcini, and the retired Republican senator Barry Goldwater, among others. On Election Day, Arizona voters backed the initiative by a margin of two to one. But the Clinton Administration attacked Proposition 200 as though it were a dangerous heresy, threatening to block its implementation and to prosecute any physicians who recommend marijuana to their patients. Clinton’s drug czar, Barry McCaffrey, called the Arizona initiative a subterfuge, part of “a national strategy to legalize drugs.”

While the Administration escalates the war on marijuana, law-enforcement officers on the front lines are beginning to question some of its tactics. Steve White served with the Drug Enforcement Administration and its predecessor, the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, for twenty-eight years before his retirement, last year. Twenty-three of those years were spent working undercover in Indiana, mainly tracking down marijuana growers. Under White’s leadership the Cannabis Eradication Program arrested more pot growers every year in Indiana than were arrested in just about any other state. White strongly condemns marijuana use and gives anti-drug lectures at high schools. But he opposes the long prison terms that first-time marijuana growers now receive. “I’m a big advocate of alternative sentencing,” he says. “For most pot growers, prison isn’t the answer. These aren’t violent people. They usually have jobs, and homes, and children. Why make their families a burden to the community?” White has learned over the years that marijuana growers come from all sorts of backgrounds and possess a variety of skills. “Put them to work, make them do community service,” he suggests. “Prison terms only strengthen their anti-establishment views.” Most commercial marijuana growers will quit the business after being caught once or twice. White feels little sympathy, however, for the unrepentant growers who are motivated by big money and the thrill of breaking the law. After a third conviction for large-scale marijuana cultivation, he thinks, alternative sentences should no longer apply. “Make prison a real pleasant place,” White says, “and keep those guys in there forever.”

The long prison sentences now given to marijuana offenders have turned marijuana — a hardy weed that grows wild in all fifty states — into a precious commodity. Some marijuana is currently worth more per ounce than gold. A decade ago the policy analysts Peter Reuter and Mark A. R. Kleiman observed that the price of an illegal drug is determined not only by its supply, demand, and production costs but also by the legal risks of selling it. As the risks increase, so does the profit. This theory has been supported by the huge rise in marijuana prices since the latest war on drugs began. In 1982 the street price for an ounce (adjusted for inflation) was about $75. By 1992 it had reached about $325. Although the costs of cultivating marijuana rose somewhat during that period, most of the 333 percent price increase represented sheer profit — the reward for evading punishment. The legal risks of cultivation have encouraged growers to produce much more potent strains of the drug, which bring a higher price and require a lower volume of sales. Growers have also found another means of reducing their risk: bribery. Throughout the nation’s rural heartland local sheriffs are being paid to look the other way during the marijuana harvest. Even local prosecutors and judges are being corrupted by drug money. The large profit margins transformed U.S. marijuana cultivation in the 1980s from a fringe economic activity into a multibillion-dollar industry — despite the fact that marijuana use was falling at the time. In Indiana the value of the annual marijuana crop now rivals that of corn. In Alabama it rivals that of cotton. The threat of long prison sentences has succeeded in making some marijuana growers rich, but it has hardly affected the availability of pot. In 1982, when President Reagan declared his war on drugs, 88.5 percent of America’s high school seniors said that it was “fairly easy” or “very easy” for them to obtain marijuana. In 1994 the proportion of seniors who said they could easily obtain it was 85.5 percent.

The Benefits of Decriminalization

HARRY J. Anslinger headed the Federal Bureau of Narcotics during the 1930s and supervised the campaign to make marijuana illegal under state and federal laws. In “Marijuana: Assassin of Youth” and similar articles Anslinger led readers to believe that the drug rendered its users homicidal, suicidal, and insane. Amid the anxieties of the Great Depression, marijuana use was linked to poor Mexicans and blacks, “inferior” races whose alleged sexual promiscuity and violence stemmed partly from smoking pot. “The dominant race and most enlightened countries are alcoholic,” one opponent of marijuana use claimed, expressing a widely held belief, “whilst the races and nations addicted to hemp . . . have deteriorated both mentally and physically.” Marijuana was the “killer weed,” a foreign influence on American life that was capable of transforming healthy teenagers into sex-crazed maniacs. Anslinger later admitted to the historian David F. Musto that the FBN had somewhat exaggerated the dangers of marijuana. Anslinger had hoped to make marijuana seem so awful and so terrifying that young people would be afraid to try it even once.

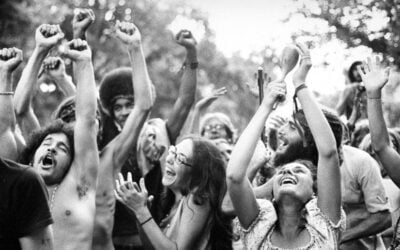

Marijuana’s “un-American” reputation has made it immensely appealing to rebellious, disaffected youth. Lurid propaganda films like Reefer Madness, Devil’s Harvest, and Marijuana: Weed With Roots in Hell, which promised a glimpse of not only the horrors but also the “weird orgies” caused by the drug, no doubt encouraged more than one brave soul to take a puff. The huge difference between the alleged and the actual effects of marijuana has long provided young people with grounds for distrusting authority. Praised by rebels and artists as diverse as Cab Calloway, Jack Kerouac, Arlo Guthrie, and Snoop Doggie Dog, marijuana has attained a lofty symbolic importance. A distinct culture has evolved around marijuana, one championed by proud outcasts. The laws aimed at that culture have only perpetuated it, enshrining the cannabis leaf as a symbol of adolescent protest.In 1970 President Richard Nixon appointed a commission to study the health effects, legal status, and social impact of marijuana use. After more than a year of research the National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse concluded that marijuana should be decriminalized under state and federal laws. The commission unanimously agreed that the possession of small amounts of marijuana in the home should no longer be a crime. “Recognizing the extensive degree of misinformation about marijuana as a drug, we have tried to demythologize it,” the commission explained. “Viewing the use of marijuana in its wider social context, we have tried to desymbolize it.” The commission argued that society should strongly discourage marijuana use while devoting more resources to preventing and treating heavy use. “Considering the range of social concerns in contemporary America,” it said, “marijuana does not, in our considered judgment, rank very high.”

President Nixon felt betrayed by the commission and rejected its findings. A decade later the National Academy of Sciences studied the health effects of marijuana and concluded that it should be decriminalized, a finding that President Reagan rejected. Nevertheless, ten states have largely decriminalized marijuana possession, thereby saving billions of dollars in court and prison costs — without experiencing an increase in marijuana use. Ohio currently has the most liberal marijuana laws in the nation: possession of up to three ounces is a misdemeanor punishable by a $100 fine. In July of last year, with little fanfare, Ohio decriminalized the cultivation of small amounts of marijuana for personal use. The change in the laws was backed by the state’s conservative Republican governor, George V. Voinovich.There seems to be little correlation between the severity of a nation’s marijuana laws and the rate of use among its teenagers. In the United Kingdom, where drug penalties are harshly enforced, the rate of marijuana use among fifteen- and sixteen-year-olds is the highest in Western Europe — one and a half times the rate in Spain and the Netherlands, where the drug has been decriminalized. The UK rate is six times as high as the rate in Sweden, a nation that has single-mindedly pursued a public-health approach to drug control. Sweden now has the lowest rate of marijuana use in Western Europe. Under Swedish law the maximum punishment for most marijuana traffickers is a prison term of three years.

Cultural factors exert far more influence on a country’s rate of marijuana use than any changes in the law. The Netherlands decriminalized marijuana in 1976 — and yet teenage use there declined by as much as 40 percent over the next decade. The rate of use among American teenagers peaked in 1979 and had already fallen by 40 percent when Congress passed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, in 1986. As young Americans became more health conscious, their use of alcohol and tobacco also declined. Since 1979 the rate of alcohol use among American teenagers has fallen by 52 percent — without any life sentences for selling beer.The conclusions of the National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse are as valid today as they were twenty-five years ago: the United States should decriminalize marijuana for personal use; possessing small amounts of it should no longer be a crime; growing or selling it commercially, using it in public, distributing it to young people, and driving under its influence should remain strictly forbidden. The decriminalization of marijuana — including, as in the Ohio model, the cultivation of small amounts — could be the first step toward a rational and sensible drug-control policy. The benefits would be felt immediately. Law-enforcement resources would be diverted from the apprehension and imprisonment of marijuana offenders to the prevention of much more serious crimes. The roughly $2.4 billion the United States spends annually just to process its marijuana arrests would be available to fund more-useful endeavors, such as treatment for drug education and substance abuse. Thousands of prison cells would become available to house violent criminals. The profits from growing and selling marijuana commercially would fall, as would the incentive to bribe public officials. But the decriminalization of marijuana is only a partial solution to the havoc caused by the war on drugs. Mandatory-minimum sentences for drug offenders should be repealed, allowing judges to regain their time-honored powers and ensuring that an individual’s punishment fits the crime. The asset-forfeiture laws should be amended so that criminal investigations are not motivated by greed — so that assets can be forfeited only after a conviction, in amounts proportionate to the illegal activity. The use of professional informers should be limited and carefully monitored. The message sent to the nation’s teenagers by these steps would be that our society will no longer pursue a failed policy and needlessly ruin lives in order to appear tough.

Decriminalizing marijuana would also help to resolve the current dispute over its medicinal use. Seriously ill patients would no longer risk criminal prosecution while trying to obtain their medicine. Although heavy marijuana use may exacerbate underlying psychological problems and may harm the respiratory system through the inhalation of smoke, marijuana is one of the least toxic therapeutically active substances known. No fatal dose of the drug has been established, despite more than 5,000 years of recorded use. Marijuana is less toxic than many common foods. Denying cancer patients, AIDS patients, and paraplegics access to a potentially useful medicine that is safer than most legally prescribed drugs is inhumane. Some of the claims made in the 1970s and 1980s about the effects of marijuana — that it causes brain damage, chromosome damage, sterility, infertility, and even homosexuality — have never been proved. Marijuana use may pose dangers that are still unknown. And yet the British medical journal The Lancet, in a recent editorial calling for the decriminalization of marijuana, felt confident enough to declare, “The smoking of cannabis, even long-term, is not harmful to health.”Although marijuana does not turn teenagers into serial killers or irreversibly destroy their brains, it should not be smoked by young people. Marijuana is a powerful intoxicant, and its use can diminish academic and athletic performance. Adolescents experience enough social and emotional confusion without the added handicap of being stoned. If marijuana use does indeed exert subtly harmful effects on the reproductive and immune systems, young people could be at greatest risk. Lying to teenagers about marijuana’s effects, however, only encourages them to doubt official warnings about much more dangerous drugs, such as heroin, cocaine, and amphetamines. The drug culture of the 1960s arose in the midst of tough anti-drug laws and simplistic anti-drug propaganda. In a nation where both major political parties accept millions of dollars from alcohol and tobacco lobbyists, demands for “zero tolerance” and moral condemnations of marijuana have a hollow ring. According to Michael D. Newcomb, a substance-abuse expert at the University of Southern California, “Tobacco and alcohol are the most widely used, abused, and deadly drugs ingested by teenagers.” Eighth-graders in America today drink alcohol three times as often as they use marijuana. Drug-education programs should respect the intelligence of young people by promoting drug-free lives without scare tactics, lies, and hypocrisy. And drug abuse should be treated like alcoholism or nicotine addiction. These are health problems suffered by Americans of every race, creed, and political affiliation, not grounds for imprisonment or the denial of property rights.At the Alabama penitentiary where Douglas Lamar Gray is imprisoned, perhaps half a dozen inmates are serving life without parole for marijuana offenses. One was given a life sentence for loading his pickup truck with ditchweed, a form of wild marijuana that is not psychoactive. Another was given a life sentence for possessing a single joint. Hundreds of inmates may be serving life sentences for marijuana-related offenses in prisons across the United States. The pointless misery extends from these inmates to their families and to the victims of every crime committed by violent offenders who might otherwise occupy those prison cells. A society that punishes marijuana crimes more severely than violent crimes is caught in the grip of a deep psychosis. For too long the laws regarding marijuana have been based on racial prejudice, irrational fears, metaphors, symbolism, and political expediency. The time has come for a marijuana policy calmly based on the facts.

Related Articles

The Rise of American Cannabis Culture

The Rise of American Cannabis Culture The modern cannabis culture is still young. After all, it was completely illegal throughout the US until 1996, when California voted to permit medicinal cannabis. And here in Colorado, we’ve only been able to operate since 2014. ...

The History of Cannabis Criminalization

It’s an unprecedented time in cannabis culture. Many of us can buy some flower or an edible at a corner dispensary right now - which would have been unthinkable in our parent’s time. As legalization progresses in the US and across the globe today, it’s...

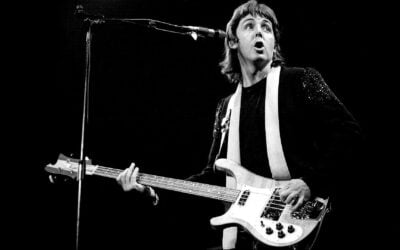

The Story of Your Favorite Rock Stars’ Cannabis Arrests

Many of our greatest creatives and musicians have used cannabis as a creative aid - and they did so at a time when consumption was still illegal in nearly every part of the globe. With the extra scrutiny that comes with life under the spotlight, this meant that...